Though human ingenuity may make various inventions which, by the help of various machines answering the same end, it will never devise any inventions more beautiful, nor more simple, nor more to the purpose than Nature does; because in her inventions nothing is wanting, and nothing is superfluous, and she needs no counterpoise when she makes limbs proper for motion in the bodies of animals. | ||

| -- Leonardo da Vinci The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci | ||

The Epic architecture is fractal.

All the applications that you develop with Epic show the same structure and obey to the same rules. A developer used to Epic can switch with almost no impedence between different applications finding in a moment what he need. A project manager can iterate the same process over and over again for both new projects and change requests. All the tiers and layers look similar.

Even the Epic’s source code shows the same structure: for example the main entry point to the domain model, the IEnterprise, is a model in a bounded context, an entity identified by its name (the corporate that uses the application). Other models in that context are the working session, the environment and the users (courtesy of Microsoft).

Fractals are all over the world, and it is obvious that a system designed to model a reality has the same structure of that reality itself.

Now, the typical architard in his ivory tower would have stated "Uhh? Fractals? What a fancy stuff! This guy has never seen a line of code! Where are the tiers? Where are the services?".

Lets give them what they need.

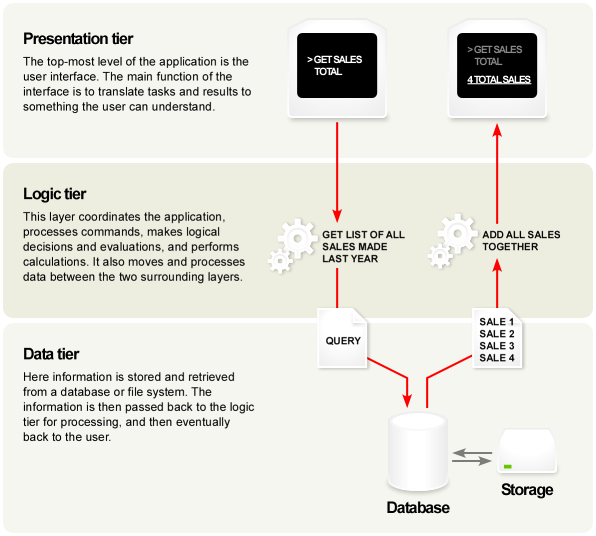

Three-tier architecture

Most of the enterprise’s applications sold out of there follow the typical three-tier architecture/configuration with a presentation tier handling the user interface, an application tier that controls the business logic and a data tier that consists of database servers.

Such architectural vision is simple enough and works so well that it became a "industry standard" for a while: it fits extremelly well the needs of ajax web sites, blogs and ecommerces, but it is also very popular in intranet applications used in many banks, insurance groups and so on.

There is nothing wrong with it. Even many Epic-based applications can be seen as examples of this architecture, but such vision would not add value to any player.

However, when the software’s complexity grows, the three-tiers abstraction looses its prescriptive value, becouse nothing is said about what happens into a single tier.

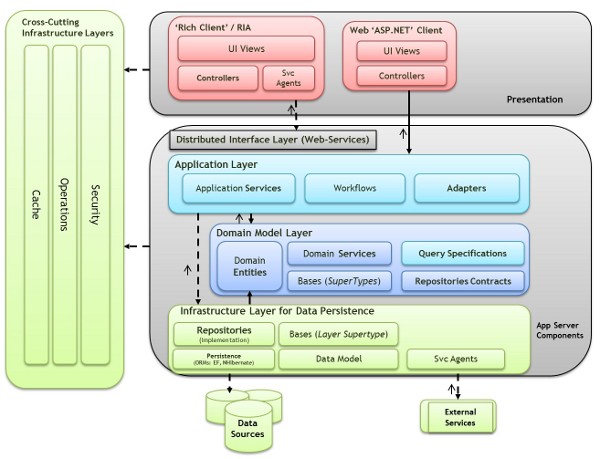

Domain Oriented NLayered .NET 4.0 Architecture

An interesting evolution of the three-tier architecture applied to corporate applications has been recently delivered from Microsoft Spain.

Microsoft Spain has noticed, in multiple customers and partners, the need to have a “.NET Base Architecture Guide” that can serve as an outline for designing and implementing complex and mission critical enterprise .NET applications with long term life and long evolution. This frame of common work defines a clear path to the design and implementation of business applications of great importance with a considerable volume of business logic. Following these guidelines offers important benefits regarding quality, stability, and especially, an improvement of future maintenance of the application, due to the loose-coupling between components, homogeneity, and similarities of the different developments that will be done based on these guidelines. | ||

| -- MSDN Architecture Center | ||

By reading the guide they provide you notice a few similarities between the Epic’s proposal and the Microsoft one. Indeed they both target corporate applications and they both promise to improve the quality, stability and to embrace the change.

For sure the guide is valuable and worth a read, since it gives a good introduction to many architectural concepts, design patterns and development tools.

However, to my money, the overall vision repeatedly proposed lacks simplicity.

I admit, many architects do not need simplicity, they need "industry standards" to support a process involving themselves to maintain the corporate standards.

However, I’ve found that a simple overall vision shared between developers, project managers and architects is even more valuable for a project than the skills of the team itself (that is, in turn, the more valuable asset for a software company).

The architectural vision proposed by Microsoft is good for architects and developers, but their stakeholders can’t grasp it.

The Onion Architecture

In July 2008, Jeffrey Palermo started a serie of post about what he called Onion Architecture. The key concept was to keep the domain model at the core of the application and everything else outside.

It was a good metaphor to describe our emerging infrastructure. We used it for a while to teach newcomers and it worked quite well.

Still, the Palermo’s pattern did not matched exactly with our systems. After some time I realized some of the differences:

- we have not one big domain, but many small bounded contexts,

- every piece of our applications can be replaced without much effect on everything else, even the domain model,

- our process makes easy to track dependencies and versioning,

- our infrastructure allows fine grained deploys.

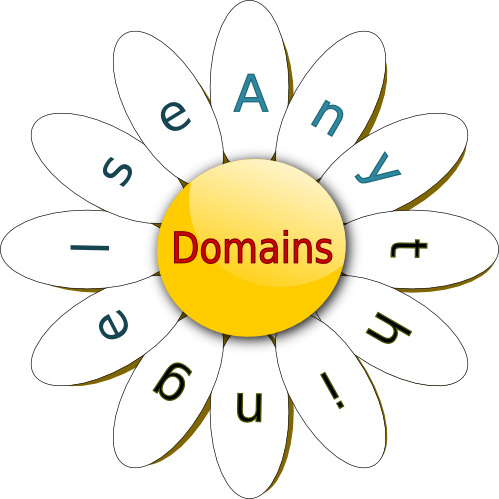

The Daisy Architecture

What is simpler than a daisy? What nicer? And what is more common than a daisy?

Bellis perennis is a common European species of Daisy, often considered the

archetypal species of that name. Although many people think that the flower

had a yellow centre with white petals this is not the case.

Each individual "petal" is itself an individual flower.

In the centre there are many tiny yellow flowers also.

Think about the domain model: in a single corporate application you might have a lot of different contexts to handle. Each context has its own content but the structure is always done of entities, value objects, domain services and so on.

Now think about this: are you sure that the same persistence tecnology would fit

the usage patterns of all these small domains? Are you sure that the same team

will build all the GUIs required?

No, you are not.

You are welcome to the best application of ingenuity that I’ve ever seen: the daisy architecture.

We are back to the fractal [9] again.

The yellow flowers at the center model the different bounded contexts that your customer requires. When requirements change, you can add, replace or remove anyone of this small domain models with little (if any) effect over the rest.

The white flowers (the petals) are the different components that make the domains available to the users, from the persistence layer to the user interface and the web services. You can replace any of this components without affecting the domain (and often the other components too).

![[Tip]](images/tip.png) | |

Epic itself is just a petal and you will be able to replace it with the next industry standard. Still, it provides a simplified domain model by itself, modeling the enterprises using your application. |

We all call "Domain Model" the flowers on the center and we call "Infrastructure" any thing else.

In this part of the manual complements the Epis source code and the API documentation. Here the different components of the Epic infrastructure will be explained in depth.

![[Caution]](images/caution.png) | |

Even if strongly based on previous "production-ready" prototypes, Epic is still work in progress. While the documentation here should be more stable than the APIs distributed up to the 1.0 release, still some changes could be done in the future. |

[9] The Epic’s source code (and the manual you are reading) can be considered as a fractal function that generates complex domain driven applications.